A Sports Card Boom That Became A Junk Wax Era

The current sports card boom isn't the first time a boom happened -- and that boom eventually became a bust.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how the sports card craze has flared up again, in part because people were looking for something to do when the pandemic resulted in so many activities and businesses shutting down.

This wasn’t the first time the sports card market went crazy.

I can remember getting back into the hobby in 1989. That was a time when there had been multiple baseball card companies putting out product, and when new companies were producing football and basketball cards.

Then, in 1990, things really took off and you could find product almost everywhere you went.

Let’s backtrack a bit to see how things got to that point. With the exception of a few years here and there, Topps was the only company producing sports trading cards through — that is, until Fleer filed in 1975 an antitrust lawsuit against Topps and Major League Baseball. A court ruling went in Fleer’s favor and a lengthy appeals process followed, which led to, in 1981, Fleer entering the baseball card market, along with Leaf.

Topps, Fleer and Leaf shared a similarity in that the three companies produced a number of candy and gum products, along with various trading cards and stickers. Fleer’s legal action against Topps allowed that company to produce baseball cards, along with Leaf, who introduced the brand Donruss.

Baseball cards became a hot commodity at that point because of the interest in older sets dating back to the 1950s and earlier. However, interest in other spots wasn’t there.

That takes us to 1988, when another company called Amurol introduced Score baseball cards. Then Upper Deck introduced its first baseball cards in 1989.

Also, in 1989, Pro Set hit the market with its first football card set. That was followed by a company called Impel releasing a basketball card set, NBA Hoops.

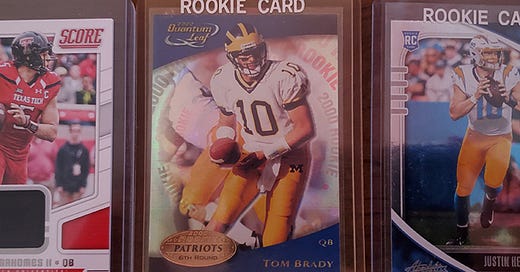

The difference with these four companies is they weren’t in the business of producing candy and gum products. They were focused primarily on trading cards. In each case, their products featured better photography, better card stock, and in the case of Pro Set and Hoops, the introduction of rookie cards for draft picks in that season (though rookie cards had been a part of baseball sets before 1989).

The sports card market took off big time, with collectors now pursuing football and basketball alongside baseball. Hockey followed in 1990 when multiple companies got trading card licenses, and football and basketball grew when more companies got licenses there.

However, the massive increase of product led to an over-saturation of the market. Certainly, you could find sports cards at plenty of retail outlets before, but now you saw stacks upon stacks of such product.

This time frame was later dubbed the “junk wax era” because so many different sets in so many sports hit the market, to the point that there wasn’t much out there that was worth a lot. Whenever something did become worth a lot, it was usually because it fell under the radar.

While the initial surge of product was good for hobby dealers at first, it became too much for them over time. The abundance of product meant that dealers were less likely to buy what collectors had to offer.

That abundance of product also caused several companies to go out of business or get bought out by other companies during the 1990s and after. For those companies that remained, they started tailoring their products so that hobby dealers got certain products that only went to them, or if a product was sold in retail outlets, they got boxes that had better odds for key “hits” such as the autographed, jersey or relic cards that gained popularity in the late 1990s.

On one hand, the “junk wax era” resulted in some creative products and card designs. It also allows for new collectors to buy relatively cheap product these days, if they just want to have fun ripping open packs to see what they get.

On the other hand, that era soured some people on sports card collecting and some retail outlets no longer wanted to carry product they couldn’t get off the shelves. Eventually, retail sales was limited to places such as Target, Walmart and Toys R Us (in the case of the third, until the company shuttered its stores). The result: It was harder to gain new, younger collectors who might be interested in joining the hobby.

Now we come to today’s market, in which Panini has exclusive deals with NFL and NBA, Topps has an exclusive MLB license (though Panini has a deal with the MLB Players Association) and Upper Deck has an exclusive license with the NHL.

This has limited product on one hand, but it means that the lack of competition gives less incentive for a company to specialize or be creative. And when it comes to “limited product,” that has less to do with the total production and more to do with the fact that you don’t see the product in every retail outlet in existence.

However, as I previously wrote, there have still been instances of product sitting on retail shelves, then showing up at discounted rates. The recent craze has changed that, but if more people become aware about the real difference between hobby and retail product, it could easily lead to people souring on the hobby, when they find out they aren’t able to get the best “hits” in retail products marked up to staggering highs.

I don’t know how long this craze will last, but the best thing for anybody entering the hobby is this: Take time to educate yourself about what is really out there, and be wary of paying too much for the products made available at Target and Walmart. That product, while not in the mass quantities of the 1990s, is still plentiful.

We may not be in a new “junk wax era,” but we could have a crash following this surge if people start realizing that retail blaster boxes, marked up too high, aren’t as good of a deal as they thought.