How to Understand Rural Voters

And why Tim Walz doesn't appeal to them as much as one may think.

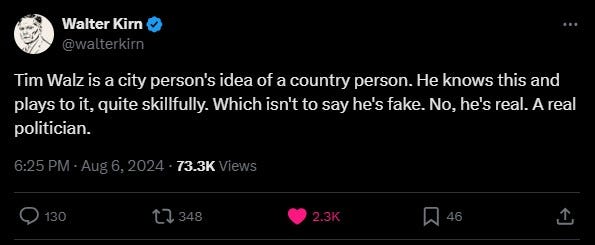

After the announcement that Tim Walz would join Kamala Harris on the Democratic Presidential ticket, I thought the best observation came from Walter Kirn about Walz and what his selection is really about.

Somebody mentioned on X — that is, The App Formerly Known As Twitter — that Walz understands rural voters, noting that he was born and raised on a farm, lived in Mankato, Minn., and coached high school football.

I’ve also seen those who believe that because Walz goes hunting and owns a gun means that Trump voters have no way to push back against him.

The problem with this pushback is that it’s not really addressing Kirn’s point. The point here is that Walz is a politician, first and foremost, and everything plays to that.

It doesn’t mean that Walz didn’t grow up on a farm, was a bad football coach or doesn’t really like to hunt. What it means that he’s the type of person who will take things about him that are true (grew up on a farm, coached football and was great at it, likes to hunt) and play it up for effect.

And that, in turn, plays right to Democratic voters who have their perceptions of what rural life is like and what appeals to rural voters. “Farming! Hunting! Football! That’s what small town America is all about, amirite?”

While it’s true that rural life can include those three things, that’s not how you actually appeal to rural voters. If you want to understand rural voters, you have to understand the basics about how they think.

I will say that rural voters will differ in certain ways, with the example being how Kirn described the difference between Walz and JD Vance, Donald Trump’s running mate for the GOP Presidential ticket. Vance grew up in poverty in Appalachia and had to work his way up, while Walz grew up on a farm and, thus, his family owned land.

I will let you listen to more of what Kirn had to say on a recent podcast with Matt Taibbi as the two went over the Walz nomination. But let me get back to rural voters.

I’m a person who grew up in Longmont, Colo., a city that had about 40,000 people at the time and would best be described as “suburban.” (It’s much bigger now and definitely not a “rural” city.) I’ve since lived in three communities that would fit the description of “small town,” those being Rocky Ford, Colo., Raton, N.M., and Kingman, Kan., all of which currently have less than 5,000 residents each. The three communities differ in certain ways, in terms of their demographics, location and economies, which means you’ll find voters there thinking differently about some topics.

But they are similar in terms of the basics about rural voters — and all three are good examples of what a rural area is really like. In all three towns — and others like them — you will find the following things to best describe their voters:

1. Rural voters like grassroots efforts.

To understand what a grassroots effort is all about, it's a "bottom up" initiative, not a "top down" one. If you take your own money to fund a political campaign, for example, and seek donations from private individuals, that's closer to "bottom up" than when you take money from special interests to fund it.

Grassroots efforts also come into play when talking about the small business owner who started with an idea and turned it into a successful business. The same holds true with the person who has a policy idea and visits with local individuals to build interest, rather than joining a think tank in Washington D.C.

When you look at the more significant changes that have happened in the United States, the majority came from a grassroots effort. Rural voters like such efforts and are more willing to listen to the ideas, particularly if you meet with them personally to sell your ideas to them.

2. Rural voters would rather rely on themselves than the government.

While rural voters can struggle to make ends mean like anyone else, they are not inclined to visit their local government offices to find out how they can get money to address it. This is particularly true if they have to go to a federal government office.

If rural voters are going to take any help from a federal agency, or even a state agency, they'd rather it be for the type of projects that the average rural voter can't do himself. The average rural voter isn't in a position to build a road, for example, so the average rural voter can accept that federal or state money might be necessary.

But when it comes to their personal lives, rural voters aren't motivated to seek government benefits to make ends meet. If you can reduce their tax burden, they are happy, but requiring them to fill out a form to get a check from the government isn't something they want to do.

3. Rural voters dislike condescension.

I hear plenty of stories about people who work in jobs that are in a rural environment, in which those people have worked the jobs for years and gained a lot of experience and insight, only for somebody in management — who went straight into management rather than work in the field and get promoted — tell said people they don't know how to do the job right.

If you spend your time lecturing rural voters about what's best for them, you're going to lose them. The same holds true if you prattle on about statistics or wave a dismissive hand when a rural voter points something out.

Rural voters don't know everything, but that applies to every person. You don't have to agree with everything a rural voter says, but sometimes that voter has good insights. It's better to listen and ask yourself "what have I been missing" than to act like you always know more than the rural voter does.

4. Rural voters want you to be straight with them.

There are plenty of times in which rural voters will engage in a conversation and find disagreement on politics. However, the rural voters all use words that are easily understood.

Those that work in the bureaucracies and for the special interests tend to use language in which it's sometimes hard to understand their points. At other times, they come off as hypocritical, in which their words don't match their actions. Either way, rural votes see these people as phony.

If you disagree with a rural voter on a policy position, you should say so, but be direct and to the point. The rural voter may not like it, but the rural voter will listen to your point.

5. Rural voters are going to notice the negative effects of policy from elites.

One of the biggest issues in the United States is the amount of policies that are set by those in charge, who then never see a negative impact. But rural voters see them all the time.

The bureaucrats and special interests set policy goals and think that everybody is equipped to handle them, but in rural areas, they are likely to lack resources. The end result is a greater burden on those areas, which then means it's harder for them to serve the needs of their citizens.

Also, the rural areas are those that are predominantly centered around one or two industries. If one or both pack up and leave town because policy favors them pulling out, the rural area goes into decline and voters get desperate. Sometimes it's a good idea to ask what happens to a community before moving forward with a policy goal you think will be nothing but positive.

6. Rural voters want to see some results to believe their voices have been heard.

People in rural areas want to see others keep their word. They want to see that something is trending in a positive direction — and certainly want to notice the impact in their communities.

This doesn't mean that a rural voter will insist upon overnight results or be unhappy if not a lot change. But they at least want to see something happen that tells them that the effort was made toward change.

If a politician keeps his or her word to push for a policy direction, but doesn't always succeed, the rural voter will still back the politician if the rural voter is convinced the politician made a real effort. But if they suspect the politician didn't make the effort, they won't be happy.

I will give you a couple of examples of what bothers rural voters. For one, there was the federal government's push to find out how many lead pipes still exist in people's homes. As the city manager discussed at city commission meetings, one bureaucrat suggested that the city go onto properties that had lead pipes, replace them, then send the homeowner the bill. The city manager wasn't the only one who thought this was ridiculous.

Another one would be the "unfunded mandate." Case in point was the state changing election laws because of concerns about ensuring ballots were cast by actual voters and doing more to restore the public's faith in election results. The problem was that they made county offices foot the bill to meet new requirements for ballots, which wasn't something our local county clerk liked, because how was the county supposed to find the money to pay for that.

But what I've discussed about rural voters should give you a better understanding not only about them, but about who is more likely to find Walz appealing. It's not the rural voters, it's not the working class voters — it's about giving Democrats another reason to feel good.

Water Kirn, once again, nails it.

This is not to say that the Harris-Walz ticket is destined to fail, but only to say that the move was not really about appealing to rural voters or the working class.

And for those wondering why I haven't had much to say about the Trump-Vance ticket, be patient. That will be a topic for next time.